What to do about Western bean cutworm in corn

Oct 21, 2021

While not native to Canada, the Western bean cutworm (WBC) has certainly made itself at home here. Originating in the Great Plains region of the U.S., it was first found in Ontario in 2008 and appeared in the Maritimes around 2017. WBC is primarily a pest of corn and dry beans, and tends to leave soybeans alone.

In corn, WBC can cause yield loss, but perhaps more seriously, its feeding behaviour can leave ears vulnerable to disease, including Gibberella ear rot (GER).

So what can you do? Start by knowing what to look for, when to look for it and, based on what you find, what your options are.

A year in the life of WBC

Thankfully, Western bean cutworms have just one generation per year. The larvae overwinter in the soil and while adult moths can emerge as early as June and late as September, the peak emergence period is mid-July.

Adult moths are active night-flyers and can often be found resting in the whorl of corn plants during the day. They are dark gray-brown in colour with a whitish stripe along the front of the forewing, a whitish dot at the mid-point of the same wing and a similarly coloured, kidney-shaped marking toward the end of the wing.

During the vegetative growth stages, females deposit egg masses on the upper surface of corn leaves; after tasseling they lay eggs on the leaves that are closest to the ear, or even on the ear itself. On average, an adult moth lays about 380 eggs in her lifetime, but some can lay as many as 600 eggs!

Newly deposited eggs are bright white and barrel-shaped with an average of about 50 eggs per mass. Just before they hatch, the eggs start to look purple, which is the colour of the larva’s head showing through the eggshell. And it’s a short timespan – eggs hatch between five to seven days after being laid.

Emerged larvae eat their shells before moving on to the corn plant. What they do at that point largely depends on the plant’s developmental stage – if the corn plant is at the VT stage, the larvae will feed on tassels and developing anthers. The good news is that WBC feeding at this stage does not result in economic injury.

However, if the tassel has emerged by the time the larvae hatch, they will settle in leaf axils where they feed on dropped anthers and pollen, and will also feed on silks. When pollen shed stops, larvae move up to the ear tip and feed on developing kernels. Mature larvae feed on the ear tip and tunnel into the ear to access the kernels. Now we’re talking economic injury.

What do they look like? In early developmental stages, WBC larvae have subdued diamond shapes along their back. As they get older, distinct dark brown bands develop just behind the head. On mature larvae, these bands look like a bisected rectangle.

It’s important to note that mature larvae can and will move to other plants, both within and across the row from the plant where they were born. WBC larvae complete six growth stages in about 55 days, then drop to the soil where they burrow in to create an earthen overwintering chamber. In coarse soils, these chambers can be as much as 40 cm deep, but the average depth across all soil types is about 20 cm. Under normal conditions, winter mortality rates are about 60%, although this can be much less in coarse soils.

Eating your yield

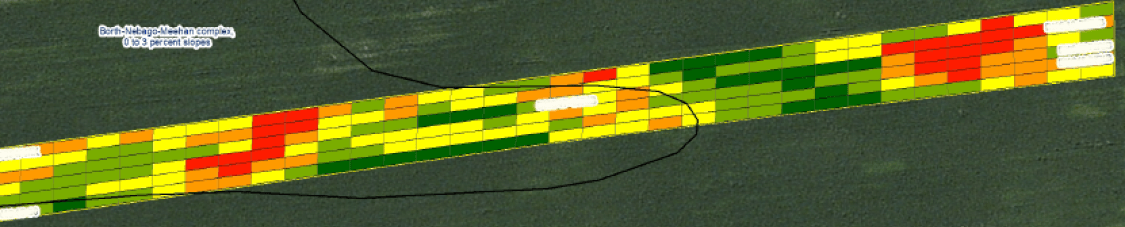

Given that larvae can migrate to neighbouring plants, crop injury from WBC is usually rather randomly distributed across a field. Most larvae are found within 1.7 m of the original plant and this movement can lead to many damaged ears scattered throughout the field. The red areas on this yield map show spots with heavy WBC infestation and give you a sense of the randomness of crop injury.

Fully mature WBC larvae destroy kernels both at the tip of and right along the ear. Unlike corn rootworm, where one larva per ear is the norm, ears infested with WBC often have multiple larvae consuming the kernels one by one. Of course, the main outcome of this is yield loss. Yield loss studies done in Nebraska have shown that a field average of one WBC larvae per plant (when the corn is at dent stage) can cause yield losses of 3.7 to 15.1 bushels per acre.1

Exposing your crop to GER

Just as serious as yield loss is how a WBC infestation exposes your crop to greater disease risk. By breaking through the husk and tunneling into the ear, WBC create entry points for disease pathogens, particularly ear rots and mycotoxins.

The mother of them all is gibberella ear rot (GER) and stalk rot, which are caused by Giberella zeae, the same pathogen that causes fusarium head blight in wheat. This fungus overwinters on the residue of corn and wheat and produces mycotoxins, including deoxynivalenol (DON or vomitoxin), which can seriously downgrade crops.

Signs of GER. Typically, the pathogen enters kernels through the silks, and if the weather is cool and wet during and after silking, there is a greater chance of infection. This pathogen will also take advantage of wounds created by birds or insects, like WBC, and get into ears that way.

Once an ear is infected, mold develops. It starts out looking white, but characteristically, it turns dark red or pink as infection sets in, and moves from the tip of the ear to the base. On severely infected plants, the ear husk and cob fuse together, making them look mummified.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has set maximum acceptable levels for DON in feed corn, depending on the end use. For instance, DON levels need to be five ppm or less for beef and feedlot cattle older than four months. For swine, young calves and dairy animals, DON levels in corn must be no more than one ppm.

You can have your harvested grain tested for mycotoxin levels, but make sure you clean it first to remove grain dust and lighter, shriveled kernels where mycotoxins are most concentrated. Even if your corn is destined for silage, a mycotoxin test is recommended. Learn more about how to identify and manage gibberella ear and stalk rot in corn here.

Managing for Western bean cutworm

Planting WBC-resistant corn hybrids is the surest way to reduce or eliminate crop damage and losses from this pest. Currently, hybrids with the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) protein Vip3A are the only Bt solution for WBC. This includes Trecepta® RIB Complete® corn hybrids, which contain this specific Bt protein and can help provide control.

Unfortunately, cultural practices, such as altering planting date and tillage aimed at destroying pupal cells, have limited value when it comes to managing WBC.

In-field WBC management. As with every crop pest, scouting is a critical practice for managing Western bean cutworm infestations. Placing pheromone traps near cornfields or accessing predictive moth emergence models can help refine the timing of scouting activities, but in general, you should scout from late June through to early August, paying particular attention to corn fields approaching the VT stage, which is when moth flight activity is high.

How to sample. You’re looking for egg masses, or small larvae, on 20 consecutive plants in five locations throughout the field. Count how many masses you find as you go, calculate the percent infestation for the field, and continue scouting on a five-day schedule until the egg-laying period is over. Note that if crop growth is uneven across the field, this period could be longer than if the crop development is uniform.

Females prefer to deposit eggs on plants that are just about to tassel. In some years, they lay eggs on whorl-stage corn but these larvae won’t survive, as feeding on vegetative tissue alone is not sufficient – they need reproductive tissue or pollen to complete development.

Should I spray? The economic threshold for spraying depends on the mycotoxin risk for your field. If it’s minimal, and your major concern is crop injury, then an application of insecticide is warranted at five to eight per cent infestation.

In areas where mycotoxins are the main concern, spray as soon as infestation reaches five per cent – and keep in mind that the economic threshold in this situation is additive. For example, if the infestation rate is two percent on the first day of sampling and five days later it’s at three percent, then you have reached five percent infestation (2 + 3 = 5) and should spray.

Also, if the risk of mycotoxin infection is high, consider including a fungicide with the insecticide and apply R1. Talk to your dealer about products and mixes as recommendations can sometimes change.

1 Journal of Integrated Pest Management, Vol. 10, Issue 1, 2019: Ecology and Management of the Western Bean Cutworm in Corn and Dry Beans – Revision with focus on the Great Lakes Region. https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/10/1/27/5558144